Visiting the American Museum of Natural History was an eye-opening experience, not because it offered the traditional museum offerings of stuffed animals, dinosaur bones and minerals, but because the AMNH provided a rare glimpse into the racial politics in America of the early 20th century.

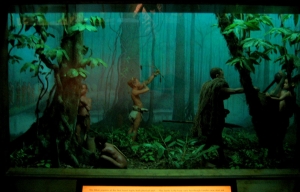

The AMNH is not just a museum of natural objects, but it is also a museum of anthropology, which turned out to be a place of jaw-droppingly cheezy titallation. Consider this "educational" diorama found in the South American section of the museum.

Presuambly, dioramas show mannequins of an ethnic group dressed in reprentative clothing, and engaged in some kind of meaningful activity. In this display of an "Amazonian woman" the woman is shown practically naked, standing in a pose that would not be out-of-place for a prostitute in a booth in the red light district of Amsterdam. This is Victorian-style pornography, pure and simple.

Classifying animals and indians

A natural history museum serves an important purpose - it organizes our knowledge of the natural world. You and I, not being professional biologists, have little knowledge of the natural world. So we come to the museum to be overwhelmed by the sheer variety of animals, gathered together in one easy convenient location.

But how was it possible to gather such an enormous variety of animals from around the world into one place? As pointed out by sociologist Bruno Latour, the ability for an 19th century British naturalist to study a variety of animal species required the existence of a fleet of ships that could circum-navigate the globe. It is, thus, no accident that the rise of the natural history museum coincides with the rise of the British Empire. Only with the reach of the British Navy, could a British naturalist travel around the world to find so many exotic species.

In the great voyages of the British circumnavigators, there was invariably an enthousiastic young naturalist amongst the crew, whose job it was to collect the bodies of strange animals and bring them back to the museum. However, these voyages were not made purely for the sake of science. The main purpose of these voyages was to find more lands to colonize. They were as much to catalogue non-European people ripe for subjugation to catalogue the animals of the earth.

In the AMNH, we can see these two historical functions of British exploration - cataloguing animals and colonialization - fuse together. The classification of animals inside a museum reflects the best classification system as understood by professional biologists. By simply noting what animal carcasses are grouped together, and what rooms that they are located in, we can glean the taxonomy systems of modern biology.

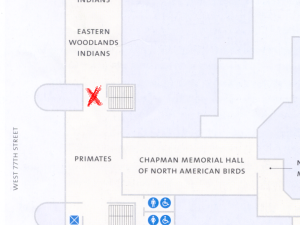

The early curators of the museum saw it fit to group monkeys with the colonialized natives. Consider this in-joke in the floor-plan of the museum. The location in the museum is the junction between the Hall of Primates and the Hall of Eastern Woodlands Indians.

Standing in the middle of the junction (the red X), you can see that the Primates room is located right across from room of Eastland Plains Indians. If you pay attention, you will see that the monkeys in the Primate room (left) are arranged in a row in a long display case set along the western wall. The monkeys are arranged in categorical order, straight out a page out of an evolution textbook, highlight the similarities of the different monkeys but also allowing the differences to show through.

This display is surreptitiously continued across the intersection into the Eastern Plains Indian room. There is an identical glass case in the Hall of Eastland Plains Indians (right), where the Indians are arranged in categorical order, just like the monkeys. The Eastland Plain Indians are another bunch of monkeys:

Educational Fantasy

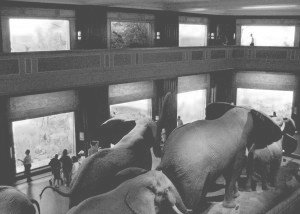

One major obstacle that prevents a museum from being a fun-and-cheery place is that it is full of dead things. A museum is essentially a mausoleum. To disguise the pervasive morbidity of showing rooms and rooms of dead animals, the curators have dressed up many of exhibits as dioramas - artificial scenes of animals faked into the illusion of life in a fascimile of their natural habitat. The specimens are massaged into life-like poses just as they would have appeared in the wild, where moldy skins are given an extreme make-over, and transformed into bodies glowing with life, and bursting with drama, action and excitement.

There is very little educational value in these dioramas. A frozen moment cannot tell us anything significant about animal behaviour. Animal behaviour is a complex thing, and really understanding requires observing an animal over time and space. That would require observing real animals in its enviroment, or studying animal biology. Instead, the dioramas feel more like trophy rooms where each diorama captures a particular moment in an African safari hunting spree, where you, the intreprid hunter, can take a pot-shot at your favourite game animal.

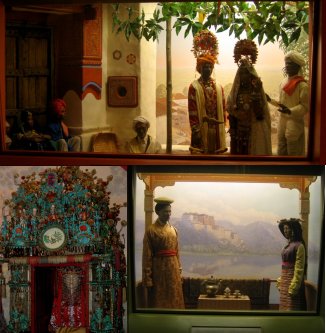

Using the same aesthetic of dressing up dead animals, the AMNH has a whole section devoted to displays of different "ethnicities". An entire culture is reduced to a single action scene. Although vastly entertaining, they capture a purity about these ethnic tribes more akin with children's books than a adult appreciation of the complexity of ethnicity. What you get is a mannequin in a fairy-tale scene. With the animal dioramas, at least the bodies are exhumed from real animals.

Given that these dioramas are more for exotic titillation, is it any wonder that many of these dioramas depict marriage scenes? Marriage is a concept that transcends many cultures and so is easy to grasp for the average museum visitor. But the best thing about marriages is the dressing-up of the bride and groom. Marriages in other cultures are so pretty - these displays are essentially glorified fashion shows:

Do they know any better?

In all fairness, this an old museum and the dioramas may be remnants of a quixotic past, where the modern-day curators are loathe to change the exhibits. Except that I found a newer section in the museum where the manner of treating other cultures ran counter to the rest of the museum. Tucked away in the back of the Museum is the Margaret Mead Hall of Pacific Islands. Margaret Mead was an anthropologist who made her name by studying the sexual lives of polynesian girls. Her work caused a major uproar in the mainly male-dominanted field and perhaps this influenced the ways objects are displayed in her Hall.

Consider these two different ways of exhibiting a ceremonial dress:

Left: we have a robe from the Pacific Islands. It is simply hung on on a rack inside a glass display. The display emphasizes the patterning and texture of the robe, and one can easily admire the craftmanship and ponder the significance of the patterns. In contrast, (Right), in the Hall of African Peoples, two matching full-bodied costumes are fitted onto mannequins. But the mannequins are posed in a ridiculous jumping motion. The absurdity of the pose completely takes away from the measured study of the costume. To display a costume in such a way shows what the curators thought were important: the jumping africans, a thought that probably had the curators chortling with laughter.

Another example is the display of head-dresses. Left: a traditional Pacific Island head-dress is displayed on a pedestal. You can study the skill and patterning involved in the fabrication of the piece. Right: an African headress is displayed over a strangely disembodied head. It looks like the head and head-dress was chopped off the original owner and taken back to the museum as booty. Is the head a cast of the actual person? Or some random representative face of someone black?

How do you show the daily life of other ethnicities? One way is to Left: use photographs to depict real life scenes in the Pacific Island. Notice how the photos acknowledge the leaking in of western society, there are tractors, and manufactured clothing. They show the adaptation to modern life. On the other hand, you can show Right: shows a "shaman" diorama from South America. It's a distinctly odd display where the shaman and child in a barely-adorned display. It looks more like rats stuck in an experimental lab-cage, where those clever anthropologists have deciphered the true meaning of shamanic magic.

Flying close to the truth

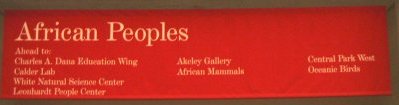

For me, a natural history museum conjures up visions of taxidermed mammals and over-sized dinosaur fossils. But it is also a place that preserves fossillized attitudes. In the AMNH the curators have no shame in putting the words "African Mammals" right next to "African Peoples", echoing a time when africans were considered more as a sub-human species of animals rather than people with complex societies and inner lives:

If you look up over the entrance of the AMNH, you will see the grand words emblazoned on facade - "Truth", "Knowledge" and "Vision". So how does the AMNH relate to truth, knowledge and vision?

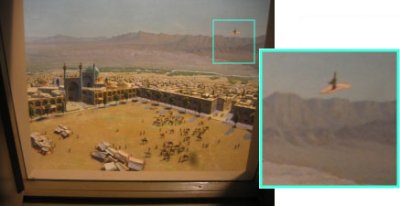

At one point inside the museum, I came across a scale model of an middle-eastern city. The model was skillfully made, and captured a myriad of details of what a medievel arabic city might look like. As my eyes wandered through the city, I noticed a little speck in the sky above the city. Yes, it was a man on a flying carpet.

The AMNH is a bastion of truth, knowledge and vision - if you believe in flying carpets.

comments powered by Disqus